Piers Kelly

University of New England

The Dynamics of Iconicity in Emergent Scripts

Abstract

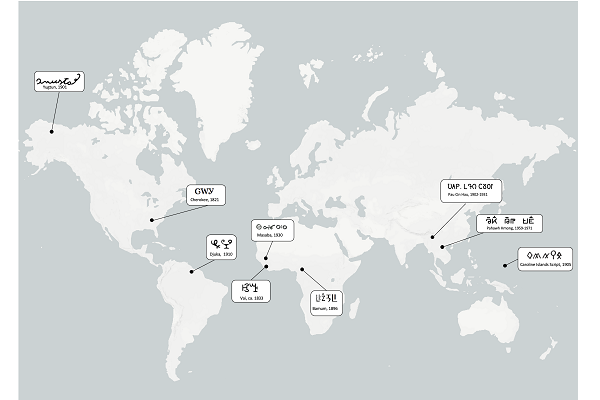

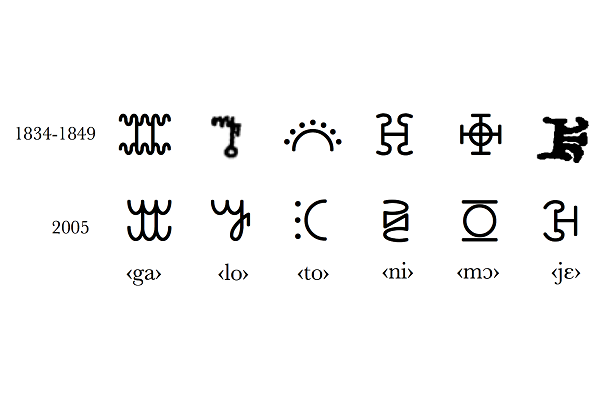

Since at least the 18th century scholars in Europe have assumed that iconicity must have played a pivotal role in early script-formation (Rousseau [1781] 1966, Pauthier 1838). Some supposed that iconicity made early scripts intuitive to invent and learn ex nihilo (Hegel [1817] 1870) but that these same icons tended to give way to abstract forms that were easier to reproduce and process (Pitt-Rivers [1875] 1906). Yet investigating the dynamics of iconicity is a vexed undertaking since the archeological record for primary scripts is incomplete and the wider semiotic context may not be well understood. Emergent scripts invented in more recent times, on the other hand, are often better documented and their historical-cultural contexts are relatively easy to access. I introduce three recent scripts invented by non-literates—Vai (created ca. 1833), Bamum (ca. 1895) and the Caroline Islands Script (1905)—to explore the relationship between their earliest sign inventories and the wider symbolic contexts in which they developed. I show that iconicity is routinely employed by naïve script inventors but that it is not the only dimension of relevance. Visual complexity is typical of early sign inventories for emergent scripts, even when complex signs are not always iconically motivated. Early signs tend to give greater prominence to raw morphology while underrepresenting sound values. This encourages the proliferation of homographic signs and suggests why rebuses and semantic determinatives are prevalent in both primary and emergent scripts.

Images Related to the Talk

Emergent scripts

Six Vai signs