Jennifer Ross

Hood College, Frederick, Maryland

On the Periphery: Communicative Practices and Signs at the Dawn of Writing in Mesopotamia

Abstract

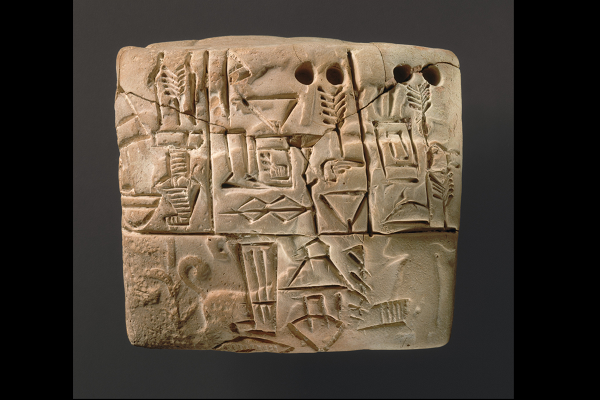

In the centuries preceding the introduction of writing, ca. 3500 BCE, residents of the geographic areas surrounding Mesopotamia, from western Iran to southeastern Anatolia, engaged in an array of regular acts that linked iconicity and identity. These acts depended on the inherent qualities of clay, malleability and durability, for their success. As was true in many other parts of the world, the main way that personal and professional identity was conveyed, and extended temporally and spatially, before writing was “invented,” was through the use of seals. Research suggests that those seals, and the practices employed in their expert usage, contained the seeds of the script that otherwise might seem to have emerged full-blown at Uruk, where the earliest cuneiform tablets have been found. Seal iconography going back to the Neolithic period provided a set of visual cues to authentication and communication, while sealing practices offered a model for the specific activities and actions that were, at last, recorded in the earliest cuneiform administrative documents. Combining image and action, seal-carvers and their patrons developed a repertoire of cognitive categories that were then drawn upon by the first scribes (themselves likely coming from the same background in communicative technologies).

Images Related to the Talk

Early sealed tablet, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art